最初ちらっと見た時には、「なんで今、聯合ニュースがアメリカの墓地の話を?」と思ったのですが、よく読むと、ニューヨークタイムズに元ネタがあったんですね。

対訳ではありませんが、韓英で並べてみます。日本語にはなっていませんので。

'도시 전체가 거대한 공동묘지'…콜마를 아시나요

송고시간 | 2016/02/07 05:49(로스앤젤레스=연합뉴스) 장현구 특파원 = 미국 캘리포니아 주(州) 북부의 유명 관광도시 샌프란시스코에서 남쪽으로 약 19㎞ 떨어진 작은 도시 콜마.

2010년 미국 인구통계국의 조사에서 1천792명이 거주하는 이곳엔 150만 개에 달하는 무덤이 있다.

현재 사는 사람보다 죽은 이들이 800배 이상 많은 콜마는 그래서 '영혼의 도시', '침묵의 도시'로 불린다. 주민들은 관광객에게 '콜마에서 살아 있는 것 자체가 대단하다'라는 우스운 문구가 박힌 티셔츠를 팔기도 한다.

일간지 뉴욕타임스는 미국프로풋볼(NFL) 챔피언 결정전인 슈퍼볼을 하루 앞둔 6일(현지시간) 죽은 자의 도시인 콜마를 소개했다. 이 신문은 제50회 슈퍼볼 경기가 열릴 캘리포니아 주 산타클라라 주변을 다루면서 이곳에서 북쪽으로 약 64㎞ 떨어진 신비의 도시 콜마를 찾아볼 만한 곳으로 곁들였다.

1924년 공동묘지로 설계된 콜마 시 면적의 73%를 차지하는 3.2㎢ 부지에 현재 17개의 묘지가 있다. 도시가 세워진 뒤 거주민이 죽은 자들보다 많았던 적은 한 번도 없다.

현재 주민들은 샌프란시스코 시 소방관 또는 인근 도시 폭주족 등 대규모 장례식 때 벌어질 만한 교통체증 정보를 전화로 통보받는다.

뉴욕타임스에 따르면, 샌프란시스코 시는 주민 건강을 위태롭게 할 수 있다는 이유에서 시내에서 시신의 매장을 금지하고, 공동묘지를 위한 부지도 허가하지 않았다.

그보다도 부동산 가격에 대한 우려가 공동묘지를 꺼린 주요 원인이었다. 1849년 골드 러시로 인구가 급증하면서 샌프란시스코는 대도시로 성장했다.

샌프란시스코 시는 1912년 한 발짝 더 나아가 이미 매장된 시신도 시 바깥으로 내쫓기로 했다. 이에 따라 이미 매장된 15만 구의 시신이 샌프란시스코를 떠나 콜마에 이장됐다.

이후 콜마의 비옥한 농토는 거대한 무덤으로 변모했다. 샌프란시스코에서 죽어 콜마에서 영원한 안식을 취하는 이들의 세계가 펼쳐진 것이다.

공동묘지엔 주지사, 시장, 상원의원은 물론 재계의 거물, 남북전쟁 당시 장군, 악명높은 알카트레즈 교도소에서 사망한 죄수 등이 묻혀 있다.

리바이스의 창업자로 '청바지의 아버지'로 통하는 리바이 스트라우스는 '평화의 집'에, 서부 개척시대의 전설적인 보안관 와이어트 어프는 '영원의 언덕'에 안장됐다.

미국프로야구에서 불멸의 기록으로 꼽히는 56경기 연속 안타의 주인공이자 배우 메릴린 먼로와의 사랑으로 유명한 조 디마지오의 비석은 '십자가 동산'에 있다.

2016/02/07 05:49 송고

http://www.yonhapnews.co.kr/bulletin/2016/02/07/0200000000AKR20160207003600075.HTML

The Town of Colma, Where San Francisco’s Dead Live

By JOHN BRANCHFEB. 5, 2016

Colma, a small town outside San Francisco, has become a necropolis for the city, which relocated the remains from four of its cemeteries there. Credit Jim Wilson/The New York TimesCOLMA, Calif. — While the Super Bowl will be played at Levi’s Stadium, and thousands of news media members who descended on the Bay Area this week were based at the Moscone Center, Levi Strauss lay inside a marble crypt in one of this tiny town’s 17 cemeteries, and George Moscone lay under the grass in another.

In a broad valley devoted largely to the dead, the history museum in Colma — nicknamed the City of Souls — sells T-shirts that read, “It’s Great to Be Alive in Colma!”

It is a town of 1,600 living residents and about 1.5 million dead ones — many of whom, like the 49ers, uprooted and left San Francisco for greener pastures to the south.

The road to Sunday’s Super Bowl stretches about 50 miles, from San Francisco, the epicenter of festivities this week, to Santa Clara, site of the actual game. The corridor, mostly along Highway 101, is a time capsule of the Bay Area’s history and its quirks — and a modern-day testament to its traffic problems.

It includes San Francisco International Airport and the Googleplex, Google’s headquarters in Mountain View. It includes the Cow Palace and Stanford University. And it includes the Hewlett-Packard Garage in Palo Alto and the Burlingame Museum of PEZ Memorabilia.

Colma has about 1,600 living residents and 1.5 million dead ones. Credit Jim Wilson/The New York TimesBut nowhere along the way may be quirkier, or filled with more history, than Colma, a quiet town of roughly two square miles covered mostly in graves. More necropolis than metropolis, the town’s worst traffic jams are caused by funeral processions; Colma residents receive warnings, by automated phone blast, whenever a big procession is expected, whether for San Francisco firefighters or an area Hell’s Angel.

Colma exists mostly because the deceased, like so many present-day workers in San Francisco, could no longer afford to live in the city.

San Francisco banned burials in the city in 1900 because the cemeteries were out of room, considered a health hazard and — more than anything — sat on prime real estate. In 1912, San Francisco announced that it would do more than ban burials. It would kick out the dead.

In the end, more than 150,000 bodies were moved from San Francisco to Colma, where farmland was turned to graveyards, the fertile soil now mostly covered in green, carpetlike grass. The number of people who die in San Francisco and spend eternity in Colma grows every day.

“All the cemeteries you go through here, they’re a history of San Francisco and of California,” said Richard Rochetta, a Colma Historical Society board member whose father emigrated from Italy and spent 30 years as a caretaker at Olivet Memorial Park.

In Colma, there are governors, mayors and senators. There are tycoons, archbishops and Civil War generals. There are architects, activists and artists. There are men once known as the Rice King, the Cattle King, the Fish King, the Beef King and the Potato King. There are Alcatraz inmates, city socialites and Phineas Gage, who was cutting a railroad bed in 1848 and somehow survived when explosive powder detonated and a 43-inch tamping iron was sent through his cheek, brain and skull before landing dozens of feet away. (His body is in Colma; his head and tamping iron are at Harvard Medical School.)

Levi Strauss is at Home of Peace, next to Hills of Eternity, where Wyatt Earp can be found. Joe DiMaggio is at Holy Cross, where his dark marble headstone this week propped up a couple of bats and two baseballs left there by fans.

A few feet behind DiMaggio is a crypt for Michael Henry de Young, founder of The San Francisco Chronicle, whose family name adorns the city’s major art museum.

Clockwise from top left: Joe DiMaggio’s burial site at Holy Cross; the Levi Strauss crypt at Home of Peace; the grave of Wyatt Earp and his wife at Hills of Eternity; and the headstone for Joshua Norton, who was also known as Emperor Norton. Credit Jim Wilson/The New York TimesNear the entrance to Holy Cross is a slate-black rectangular stone for Edmund G. Brown, the former California governor and father of the current one. Near the back is a small pink stone nestled in the grass for Moscone (“We love you Dad”), the San Francisco mayor assassinated along with the gay-rights activist Harvey Milk in 1978.

Next door, at Cypress Lawn, is a Greek-inspired marble tomb surrounded by 16 Ionic columns. It has no name on it but houses William Randolph Hearst, his parents (who built it) and other family members.

Not far away, past the angel of grief embracing the grave for Jennie Roosevelt Pool (a cousin of Theodore Roosevelt), is the baseball player and manager Lefty O’Doul. His marker lists his batting average and says, “He was here at a good time and had a good time while he was here.”

Steve Silver, creator of the long-running San Francisco musical revue “Beach Blanket Babylon” — the media center at the Moscone Center has a large display of it this week — lies nearby.

History, though, rests largely with thousands of the earliest San Francisco residents, buried in unmarked graves. When San Francisco flourished following the arrival of the 49ers (the gold-seekers of the 1800s, not the football team), the city had four major cemeteries near what is now the University of San Francisco.

Those four cemeteries — Calvary, Laurel Hill, Masonic and Odd Fellows — were a mess by the late 1800s, untended and scavenged. They were also full, and the city was still growing. The land was too valuable for the dead.

(There are two cemeteries remaining in San Francisco: the Golden Gate National Cemetery for veterans at the Presidio and a small one at Mission Dolores.)“The cemeteries had all fallen into disrepair, essentially because they relied on new plots to make money for their upkeep,” said Maureen O’Connor, president of the Colma Historical Association.

Grave markers for sale in Colma. Credit Jim Wilson/The New York TimesSan Francisco cemeteries bought land south of the city and established new ones. From about 1920 to 1941, the big four cemeteries moved roughly 150,000 bodies. Graves and markers of the deceased whose families paid to have them moved (generally $10) were replanted 15 miles south, sometimes after a solemn procession.

But most of the dead were dug up, moved and reburied in mass graves. Many grave markers, with etched names and dates, never left San Francisco. They were used to build drain gutters at Buena Vista Park and to bolster the breakwater near St. Francis Yacht Club. Some are occasionally spotted at low tide in the sand along Ocean Beach.

A monument at Holy Cross in Colma today reads: “Interred here are the remains of 39,307 Catholics moved from Mt. Calvary Cemetery in 1940 and 1941 by order of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Rest in God’s Loving Care.”A similar mass grave marked by an obelisk at Cypress Lawn, with the remains of an estimated 35,000 former San Franciscans, is said to include the headless body of Gage; Senator David Broderick, killed in an 1859 duel with Chief Justice David S. Terry of the California Supreme Court; and Andrew Smith Hallidie, considered the inventor of the San Francisco cable-car system.

By 1924, Colma was incorporated (first as Lawndale, reverting to Colma in 1941), and it has never had more living residents than dead ones.

Always a place friendly to florists and monument makers, and a bar called Molloy’s that dates to 1883, Colma began attracting car dealerships and strip malls on its western edge, near Interstate 280, in the 1970s. The train line that once carried dead bodies to Colma is now the BART line that carries living residents to neighboring cities on the Peninsula.

Supported by a commercial sales tax (but not from the cemeteries, which are nonprofit), Colma is a neat and tidy town, with three small neighborhoods and 17 sprawling, manicured cemeteries, including one for pets. Residents know that it is the dead that set Colma apart from its suburban neighbors.

“We are the city of souls, but we are really protecting the cemeteries,” said Helen Fisicaro, Colma’s vice mayor. “There is an emotional attachment to them.”There are no famous football players known to be interred in Colma. But there is Burl Toler, the N.F.L.’s first black on-field official, who worked Super Bowl XIV. And despite famous residents such as Strauss and Moscone, Colma really has little to do with Sunday’s Super Bowl.

But it is on the road to it, for those able to pass through without stopping forever.

Correction: February 5, 2016

An earlier version of this article misstated the substance that exploded and caused a head injury to Phineas Gage in 1848. It was black powder, not dynamite, which was not yet invented.

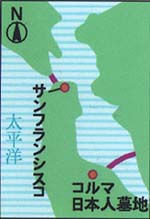

ただ、このコルマには、日本人墓地もあって、そちらは日本語でも検索すればいろいろ出てきます。

探し当てた水夫の墓

サンフランシスコ市街から南へ約三十キロ。サンマテオ郡コルマの丘に目指す日本人墓地はあった。

門を入ってすぐ、正面に大理石の墓碑が三つ。一八六〇年、咸臨丸で太平洋を渡り、この地で没した男たちが寄り添うように眠る。塩飽佐柳島の水夫富蔵、同じく塩飽広島の源之助、長崎の火夫峯吉。カーネーションと小菊が墓前に揺れている。

□ □

峯吉をはさんで富蔵(左)と源之助(右)の墓。咸臨丸の水夫らに線香を手向ける岡さん=カリフォルニア州コルマ「今でこそちゃんとまつられていますが、墓の在りかさえ分からない時があってね」

線香を手向けた岡省三さん(82)は問わず語りに墳墓の来歴を話し始めた。滞米七十年余の元銀行マン。日系移民史の生き字引といわれ、サンフランシスコ日米史料館の館長を務めている。

「日本海軍咸臨丸之水夫」と刻まれた源之助の墓を指でなぞり、岡さんは続けた。「この白っぽい部分。ここだけが地表に出ていたあかし。探し当てたのは文倉さんです」。

文倉平次郎。サンフランシスコ福音会の書記をしていた彼が客死した水夫の存在を知るのは一八九八年。富蔵と峯吉の墓が偶然見つかったのがきっかけだ。資料を調べた文倉はもう一人、源之助の名に行き当たる。苦難の航海で衰弱した三人が到着後ほどなく息を引き取った、と記録は伝えていた。

「源之助はどこかに埋もれている」。直感した文倉は墓地事務所の助手を志願して古い埋葬帳を繰り、広大な丘を探し歩いた。墓碑の頭が砂からのぞいているのを見つけたのは一年後。よほど感動したのだろう。「明治三十一年五月二十七日午後四時ごろ」と日時を書き留めている。水夫が亡くなって三十九年の歳月が流れていた。

□ □

帰国後、会社勤めをしながら咸臨丸資料の収集に奔走。塩飽の島々を訪ね、水夫の子孫から聞き取りを重ねた。昭和十三年、退職金をはたいて出版した「幕末軍艦咸臨丸」は今も咸臨丸研究の原典として類書の追随を許していない。

司馬遼太郎は小文「ある情熱」にこう記している。これほどの名著が<専門家でもなんでもないひとによって書かれたということについて、人間の情熱というもののふしぎさを、書棚でこの本の背文字を見るたびに考えこまされる>。

一人の市井人を咸臨丸に駆り立てた情熱。出発点は無名の水夫たちへの素朴な共感だった。それを終生の情熱に変えたのは、咸臨丸の存在そのものを忘れようとしている歴史への痛憤だったに違いない。

旧幕が派遣した咸臨丸の事績に明治政府は冷たく、文倉は散逸していた資料の探究に四十年近くを費やしている。あまりに不当な忘却。その象徴が遠い異郷に人知れず埋もれていた水夫の墓だった。

□ □

「ここに立つと、日本とアメリカの来し方をいやでも思うよ」。移民の墓が並ぶ丘で、岡さんの回想は続いている。

日米が国交をひらいて百四十年。この間、両国が幸福な関係を持った時間はそれほど長くない。激しい排日運動と太平洋戦争、戦後の経済摩擦。排斥と対立の軌跡を身を持って知る岡さんは「それでも」と言う。

「良くも悪くも対米関係を基軸に日本は歩み、ここまでになった。その第一歩を刻んだのが咸臨丸と乗員。日米交流の先駆者としてもっと思い起こされていいのに、日本からの墓参はめったにない」。岡さんの胸にも、文倉に重なる義憤が宿っている。

サンフランシスコ湾から駆け上がってくる風がにわかに湿りを含み、墓石を濡らし始めた。雨に煙る丘にたたずんでいると、思いは百四十年前に引き戻される。

塩飽水夫はなぜ、どんな思いで未知の海に挑んだのか。屈強な海の男を死に追いやった航海はどれほどすさまじいものだったのか。

http://www.shikoku-np.co.jp/feature/shimabito/1/1/