某所で見かけたワシントンポスト紙のこの記事。ちょっと長いですけど、バランスもとれれて興味深いです。

一部日本サイドから仕掛けられている「歴史戦」とやらがいかに情勢分析を怠った「自滅の戦い」であるか、その構図が透けて見えてくる記事であると思います。

- 作者: 渡辺銕蔵

- 出版社/メーカー: 中央公論社

- 発売日: 1988/09

- メディア: 文庫

- この商品を含むブログを見る

このあたりのことは、確か毎日新聞の澤田克己さんも書かれていたように思います。

- 作者: 澤田克己

- 出版社/メーカー: 文藝春秋

- 発売日: 2015/01/20

- メディア: 単行本

- この商品を含むブログ (2件) を見る

Why Japan is losing its battle against statues of colonial-era ‘comfort women’

By Adam Taylor September 21

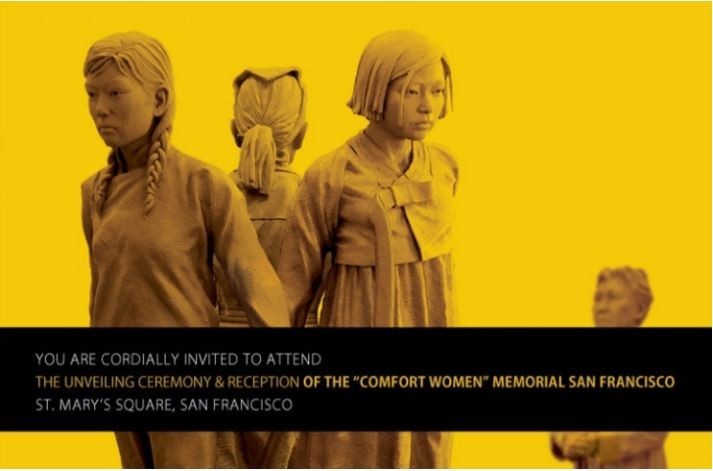

An invite for the unveiling of a statue in San Francisco that would be the first “comfort women” statue in a major U.S. city. (Courtesy of the Comfort Women Justice Coalition).Controversial statues aren't just coming down in the United States. They are also going up. And the fierce debate they provoke isn't just among Americans.

A statue in San Francisco to be unveiled Friday has prompted behind-the-scenes recriminations from Japan, including attempts by the local Japanese Consulate to block its installation and alleged harassment from Japanese conservatives half the world away.

Jun Yamada, the Japanese consul general in San Francisco, told WorldViews that the installation was “destined to be yet another addition to the existing quagmire surrounding 'controversial statues.'" A spokesman for Japan's Foreign Ministry said the statue was “regrettable and incompatible with the position and efforts of the government of Japan.”

But what makes the statue so controversial? Located in St. Mary's Square and created by Californian Steven Whyte, it looks simple enough: a depiction of three young girls with a grandmother figure standing nearby.

An inscription on the side of the statue offers a clue about what prompted Japan's angry response.

“This monument bears witness to the suffering of hundreds of thousands of women and girls euphemistically called 'Comfort Women,' who were sexually enslaved by the Japanese Imperial Armed Forces in thirteen Asian-Pacific countries from 1931 to 1945,” the inscription reads.

This would be the first “comfort women” statue in a major U.S. city. It is part of a growing trend: Statues dedicated to Japan's wartime sex slaves have cropped up worldwide over the past six years. There are reported to be 40 in South Korea and 10 in the United States, including in Virginia's Fairfax County, New Jersey and Southern California.

For Japan, which cares greatly about its soft power and global reputation, these statues are a problem. But why is Tokyo losing the battle against them?

How the statues spread

South Koreans gather near a statue symbolizing wartime sex slaves during a protest in December 2015 outside the Japanese Embassy in Seoul over an agreement between Japan and South Korea over the issue. (Jeon Heon-kyun/EPA)Mainstream historians say that as many as 200,000 women and girls from occupied countries such as Korea, China and the Philippines were forced to work in brothels run by the Japanese Imperial Army. Though once rarely acknowledged, survivors of these brothels began to speak publicly about their experiences in the 1990s, and soon there were widespread demands for Japan to apologize for the wartime practice.

However, it wasn't until 2011 that the first statue memorializing comfort women appeared. A bronze likeness of a girl sitting by an empty chair was placed outside the Japanese Embassy in Seoul. The empty chair allowed a visitor to sit alongside the young victim. Some supporters put winter accessories on the girl, as if to protect her from the cold. The statue was installed to commemorate the 1,000th weekly demonstration outside the embassy by survivors and supporters demanding an apology from the Japanese government.

Though other monuments dedicated to the memories of sex slaves have been in existence for long, something about this statue appeared to capture the public's imagination in a different way.

Soon, statues with the same design were mounted in as far as Germany and Australia. “That is what these memorials are about,” said Mary McCarthy, an associate professor at Drake University who studies the movement behind the statues. “Helping to spread awareness through our emotional connection with the stories of these women.”

Though the San Francisco statue does not have the same design because of local requirements that public artworks must be unique, it fits into this tradition: The three girls in the statue represent women from Korea, China and the Philippines, while the grandmother symbolizes the survivors still hoping for justice.

That justice has proved elusive. A 1993 statement by then-Chief Cabinet Secretary Yohei Kono acknowledged imperial Japan's use of sex slaves after a government study into the issue and offered “sincere apologies and remorse” to those affected. In 2015, Japan and South Korea “finally and irreversibly” reached an agreement under which Japan pledged to contribute $8.3 million to a fund for the 46 surviving South Korean victims.

However, the agreement has been criticized by activist groups, which said they had not been consulted enough.

Modern-day problems

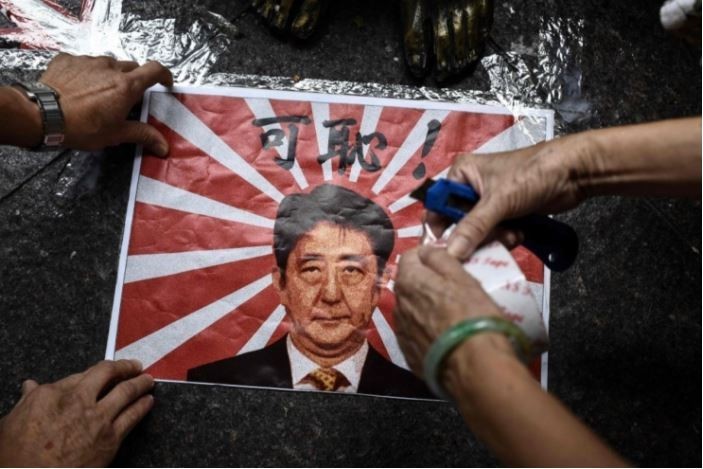

An image depicting Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and the Japanese wartime imperial flag is taped next to the feet of a “comfort women” statue before a protest in Hong Kong on Sept. 18, 2017. (Anthony Wallace/AFP via Getty Images)Ironically, Tokyo's anger about the statues might have aided their spread. “My sense is that the [Japanese government's] fixation on the statue increased its significance to activists,” said Celeste Arrington, a professor of international affairs at George Washington University.

Comfort women statues in South Korea have sparked a diplomatic row with Japan, which claimed that they violate Seoul's obligations under the Vienna Convention. In January, Japan withdrew its ambassador from Seoul in protest over the installation of a monument to the wartime slaves in the South Korean city of Busan.

Comfort-women monuments installed in the United States have sparked a similar backlash. In March the Supreme Court declined to review a case in which the plaintiff sought the removal of a comfort-women statue installed in Glendale, Calif.

A lower-key campaign was launched against the San Francisco statue. The Japanese Consulate tried to block the installation, while the San Francisco Arts Commission received numerous emails — most appearing to be from “individuals in Japan,” according to a spokeswoman — in opposition to the statue. Reporters covering the matter also have complained of receiving hundreds of emails in a similar vein.

“It may be 2017, but Japan is still fighting to deny and erase this egregious war crime and basically waiting for all the “Comfort Women” to die, so they don’t need to acknowledge the government’s responsibility,” Lillian Sing and Julie Tang, two retired judges who are chairs of the Comfort Women Justice Coalition (CWJC), which organized the installation of the statue, said in a statement.

The issue is especially touchy in San Francisco, which has a long-standing Japanese American community. Notably, though previous such statues have been installed by campaigns led by Korean Americans, CWJC bills itself as multiethnic and is led mostly by Chinese Americans.

Yamada, the consul general, said Japan takes the issue of “comfort women” seriously and stressed that it is continuing to pursue reconciliation with the victims. The problem, he said in a prepared statement, is that Japan's role is presented in a “one-sided” manner. “Unfortunately, the aim of current comfort women memorial movements seems to perpetuate and fixate on certain one-sided interpretations, without presenting credible evidence, in the form of physical statues,” he said.

In recent years, the Japanese government has promoted the idea of “cool Japan” in a bid for nonmilitary, soft power overseas. But the grass-roots movement to install comfort-women statues undermines that effort, reminding the world of some of the darkest moments in Japanese military history.

“They have a strong sensitivity to how Japan is seen in the world. They see this as tarnishing Japan,” said Jennifer Lind, author of “Sorry States: Apologies in International Politics.” "[But] the more they try and squelch this? That's actually what ends up tarnishing Japan.”